In the last post, I described the basic idea for the programming language and ideas I had. This post will start actually writing some code. Mostly covering the Lexer/Tokenizer. However in order to begin the development process of making a programming language we have to discuss a few quick things about how it’s going to be built and compiler design in the most overarching sense. Those experienced or knowledgeable in the field probably can skip the explanation.

What does the compiler do?

From a bird’s eye view, what a compiler does to take a code file and compile it into binary form is rather simple. You first take the file, read it into memory, and then split up the tokens of the language (this is stuff like int or ; and identifiers and literals). This first step is called “tokenization”, “lexing”, or “lexical analysis” (use this to sound smart). The next part is to then take this list of tokens and then parse it into an abstract syntax tree. This means enforcing the language grammar — this is where a lot of the syntax errors will probably be found, especially that missing ; on line 45. The parser parses into more abstract concepts like “Expression”, “Prototype”, “Function Definition” and other ideas.

From this step there can be additional passes to check things at compile time like not allowing you to use an uninitialized variable and enforcing a static type system. This is called “semantic analysis”. Once this analysis is done, you can hop into code generation — which usually emits some sort of intermediary representation of your code. For GCC this is GIMPLE and for LLVM this is their IR and MLIR. We will be using LLVM because it is open source and a highly performant and multiplatform compiler backend.

Once you generate this IR code there are many passes that can be ran over this code in LLVM like optimization passes and emitting formats. You can also run the LLVM JIT Compiler at this stage and call it a day if you really want to. Past this phase we emit an object file (.o) which tries to parse an object file, resolve missing names (function/data resolution), and finally emits a binary file which you can run.

Starting Lexical Analysis

Obviously I can’t cover all this in a single article — that’d be a bit absurd. We’re just gonna look at lexing for now and a sample file. So let’s make a brief language sample.

fn add(a: i32, b: i32) -> i32 {

return a+b;

}

fn main() -> void {

return add(1, 2);

}

Since we’re going to use LLVM for compiling, I’m going to have to write the compiler in C++(!). Currently I’m using Zig as the build system as it is a drop-in C and C++ compiler. I’ve named the language “Elyra” after the constellation “Lyra” which is a name referencing the “Lyre” a musical instrument like a harp. The name Lyra references beauty, harmony, and artistic expression. It’s called Elyra because the name Lyra is taken by an academic paper.

For our C++ program, I’m going to skip the details of “main” and setting up the code for now — it’s pretty much a generic console program. The first interesting structure to define is what is a token?

What is a Token?

The token for me has two main purposes, it has to have a Type and Value. The Type indicates if it’s a keyword or special character. The value holds the actual value for things like identifiers, numbers, and more. Beyond this basic functionality a Token should probably have useful metadata like the line number and column. This is helpful for syntax errors being able to point to the exact area of an issue!

struct Token {

TokenType type;

std::string value;

Type valueType;

size_t line, column;

};

Of course you’ll notice here I’ve used std::string for the value. For now that’s okay because we can just parse out a string into numbers. The valueType field holds any type data for the Type token. These are the types I discussed in the previous article. The other type I used is TokenType which is an enum defined here:

enum class TokenType {

Fn,

Pub,

Type, // any of u8, i8, f32, bool, etc.

Ident,

StringLiteral,

LParen,

RParen,

LSquirly, // {

RSquirly, // }

Semicolon,

Colon,

Comma,

Add,

Sub,

Mul,

Div,

RTArrow, // Return type arrow

Eof // Special

};

This enumeration holds every piece of data required for the program we described earlier. To actually tokenize this we’re going to create a class called Lexer which contains methods to parse a file into tokens.

The Lexer

class Lexer final {

private:

size_t line, column;

std::string current_token;

std::vector<Token> &tokens;

auto add_token_default() -> void;

auto check_special_tokens(char c, size_t &i, const std::string &buffer)

-> bool;

auto check_string_literal(char c, size_t &i, const std::string &buffer)

-> bool;

auto filter_keyword(Token &tok) -> void;

public:

Lexer(std::vector<Token> &tokens);

~Lexer() = default;

auto lex_file(const std::string &path) -> void;

auto lex(const std::string &buffer) -> void;

};

The internal state of Lexer simply keeps track of the current token, line, column, and a reference to a vector of Tokens. A Lexer does not own the Token list. It has simple methods to add a default token (which is just an identifier), checking for special character tokens, string literals, and filtering keywords out of identifiers.

lex_file isn’t that interesting of a method — it just loads a whole file into a string and throws it to the main lex method.

auto Lexer::lex(const std::string &buffer) -> void

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < buffer.length(); i++) {

auto c = buffer[i];

if (c == '\n') {

add_token_default();

line++;

column = 1;

} else if (c == ' ') {

add_token_default();

column++;

} else if (c == '\t') {

add_token_default();

column += 4;

} else {

if (check_special_tokens(c, i, buffer))

continue;

if (check_string_literal(c, i, buffer))

continue;

current_token += c;

column++;

}

}

add_token_default();

tokens.push_back(

Token{ TokenType::Eof, "", Type::void_, line, column });

for (auto &token : tokens) {

filter_keyword(token);

}

}

The lex method is pretty digestible — it iterates over the buffer and pulls out the current character. If the character is new line, space, or tab, it updates the line / column metadata, and attempts to add a token. Otherwise we check if there’s any special tokens or string literals. If there are any, these methods automatically add them. Otherwise we’ll just add the current character to the token buffer and increase the column count. After the method finishes we just make sure to add a token if any exists and push the end of file token. We then filter our identifiers into keyword and type tokens.

Of course let’s have a look at how we’re grabbing the actual tokens in add_token_default:

auto Lexer::add_token_default() -> void

{

if (current_token == "")

return;

tokens.push_back(Token{ TokenType::Ident, current_token, Type::void_,

line, column - current_token.length() });

current_token = "";

}

This block isn’t that difficult — all we do is check if the current_token has a value, then push back an identifier with the current token. Importantly we subtract the token length from the column so it always points to the beginning. After this we consume the current_token and set it to empty. (Perhaps .clear() is better — not really sure the performance difference)

The check_special_token method is literally a switch case with a case for each special character. The only notable exception is - which also needs to check for the return arrow ->

case '+': {

add_token_default();

tokens.push_back(Token{ TokenType::Add, "+", Type::void_, line,

column++ });

return true;

}

case '-': {

add_token_default();

if (buffer[i + 1] == '>') {

tokens.push_back(Token{ TokenType::RTArrow, "->",

Type::void_, line, column });

i++;

column += 2;

return true;

} else {

tokens.push_back(Token{ TokenType::Sub, "-",

Type::void_, line, column++ });

return true;

}

}

We’ll ignore check_string_literal because it’s not useful for this sample. The method in general is to find a " character and then continue reading until you find the ending " or erroring if you find a '\n' before the end of the string literal (indicating a run-on string). The next method that’s important to understand is filter_keyword which sorts through tokens and if it finds an identifier (our default token type) checks it and sorts it into keywords or value types.

auto Lexer::filter_keyword(Token &tok) -> void

{

if (tok.type != TokenType::Ident)

return;

std::unordered_map<std::string, TokenType> baseKeyword = {

{ "fn", TokenType::Fn }, { "pub", TokenType::Pub }

};

if (baseKeyword.find(tok.value) != baseKeyword.end()) {

tok.type = baseKeyword[tok.value];

return;

}

// clang-format off

std::unordered_map<std::string, Type> vtypeKeyword = {

{ "u8", Type::u8 },

{ "u16", Type::u16 },

//...

};

// clang-format on

if (vtypeKeyword.find(tok.value) != vtypeKeyword.end()) {

tok.type = TokenType::VType;

tok.valueType = vtypeKeyword[tok.value];

return;

}

}

Here we first check if it’s an Identifier. If it’s not we do not care. Then we check the list of keywords which is just an unordered_map. Unordered map was chosen because it performs better in string searches and order of the map is not important here. If it’s found it sets the keyword value otherwise it checks if there’s a value type keyword.

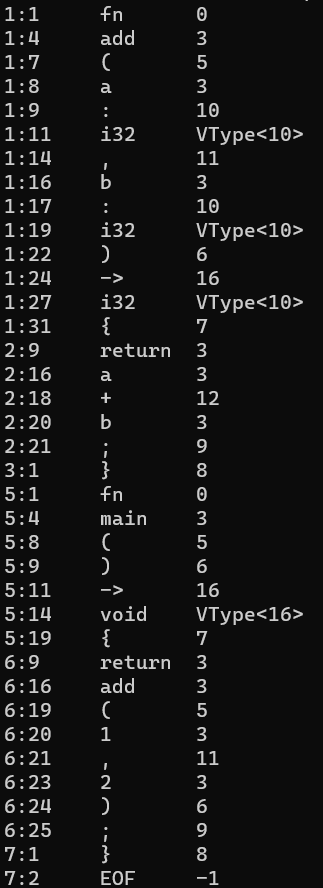

Finally I made a method to print out the tokens by line and column numbers, the value of the token, and then the type. If the token is a type then the type number is replaced with an annotation that it is a type and gives the type value.

Here’s the program in action!

That’s it for now…

I’ll be continuing to work on Elyra into the future and cover parsing and the abstract syntax tree in part 3.